| History of Translating the Bible into Irish |

|

|

Celtic Versions in Irish

The Book of Kells (in the Library

of Trinity College Dublin) (Wikipedia)

is the all-surpassing masterpiece of Celtic illuminative art and is acknowledged

to be the most beautiful book in the world. This copy of the four Gospels was

long deemed to have been made by the saintly hands of Columcille, though it

probably belongs to the eighth century. Into its pages are woven such a wealth

of ornament, such an ecstasy of art, and such a miracle of design that the book

is today not only one of Ireland's greatest glories but one of the world's

wonders. After twelve centuries the ink is as white and lustrous and the colours

are as fresh and soft as though but the work of yesterday.

|

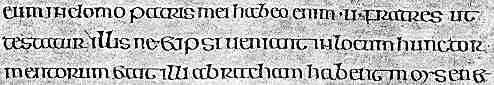

The Gospels of MacRegol, of c.800

A few lines from the Gospels of MacRegol, of c.800 (Bodleian Library, Auct. D. 2. 19). (From Thompson 1912) The above example is a relatively late specimen of the insular half uncial script, which was replaced for these works with the more compact but still elegant insular minuscule. |

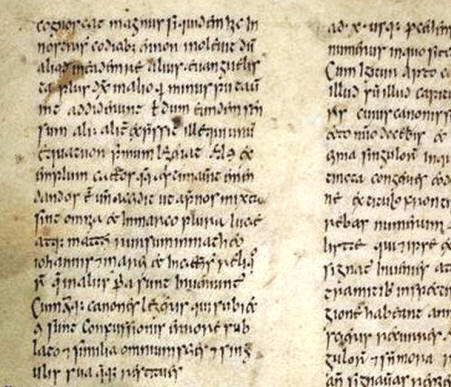

The Book of Armagh, containing portions of the

New Testament, among other things, was written in a tiny, compressed and

abbreviated, pointed insular minuscule, designed to fit as much text into a page

as possible. This is the earliest dated example of this script, indicating that

the change from large rounded letters to narrow compressed ones was not a

gradual evolutionary process, but the solution to a problem. Segment from the Gospel of Matthew, from the Book of Armagh, dated 807. (From Thompson 1912) A PDF of the entire document is available here http://digitalcollections.tcd.ie/content/26/pdf/26.pdf |

| There currently is some research being carried out by the University College of Cork relating to early Latin-Irish translation work. |

|

Early Building Blocks Of The English Bible In The British Isles By Pastor David L. Brown, Ph.D. Background work describing translation work through the first millennium. |

| The Gospels of MacDurnan (now in the Archbishop's Library at Lambeth) is a small and beautiful volume which was executed by an abbot of Armagh who died in the year 891. A full-page picture of the Evangelist precedes each Gospel, and a composite border frames each miniature in a bewildering pattern of intertwining strapwork and wonderful designs of imaginary beasts. Ornamental capitals and rich borders give a special beauty to the initial pages of the Gospels. |

|

The Gospels of St. Chad (in the Cathedral Library at Lichfield) and the Gospels of Lindisfarne, which are "the glory of the British Museum", form striking examples of the influence of Celtic art. St. Chad was educated in Ireland in the school of St. Finian, where he acquired his training in book decoration. The Gospels of Lindisfarne were produced by the monks of Iona, where St. Columcille founded his great school of religion, art, and learning. This latter manuscript is second only to the Book of Kells in its glory of illuminative design, and, from its distinctive scheme of colours, the tones of which are light and bright and gay, it forms a contrast to the quieter shades and the solemn dignity of the more famous volume. |

|

The Book of the Dun Cow, The Book of Leinster, and the other great manuscripts of the eleventh, twelfth, and thirteenth centuries are interesting as literature rather than as art, for they tell the history of ancient Erin and have garnered her olden legends and romantic tales. It is only the Gospels and other manuscripts of religious subjects that are illuminated. In the apparel of the ancient Irish, the number of colours marked the social rank: the king might wear seven colors, poets and learned men six; five colours were permitted in the clothes of chieftains, and thus grading down to the servant, who might wear but one. All this the scribe knew well. We can picture the humble servant of God, clad in a coarse robe of a single colour, deep in his chosen labour of recording the life and teachings of his Master, and striving to endow this record with the glory of the seven colours which were rightly due to a King alone. As we gaze on his work today its beauty is instinct with life, and the patient love that gave it birth seems to cling to it still. The white magic of the artist's holy hands has bridged the span of a thousand years. |

| Ancient Gaelic versions of the Psalms, of a Gospel of St. Matthew, and other sacred writings with glosses and commentaries are found as early as the seventh century, Most of the literature through subsequent centuries abounds in Scriptural quotations. A fourteenth-century manuscript, the "Leabhar Braec" (Speckled Book), published at Dublin (1872-5), contains a history of Israel and a compendious history of the New Testament. It has also the Passion of Jesus Christ, a translation from the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus. Another fourteenth-century manuscript, the "Leabhar Buide Lecain", also gives the Passion and a brief Old-Testament history. Some scholars see in these writings indications of an early Gaelic version of the Scriptures previous to the time of St. Jerome. |

|

A Modern Irish New Testament, was begun from the original Greek by John O'Kearney (or Kearney, or Carney; d. 1600?), in 1574, Nicholas Walsh (later Bishop of Ossory; d. 1585), and Nehemias Donellan (later Archbishop of Tuam), and finished by William O'Donnell (or Daniell; d. 1628) and Mortogh O'Cionga (King), was printed in 1602. |

|

An Old-Testament version from original sources was produced by Dr. William Bedell (1571–1642) with the assistance of Murtagh King and Dennis Sheridan and was published at London (1686). It was revised by Andrew Sall (1612–82), Narcissus Marsh (1638–1713), and others. A second edition in Roman characters was published (1790) for the Scottish Highlanders.

|

| An Irish version of Genesis and Exodus was made by Connellan (London, 1820). |

|

And a catholic version of Genesis through to Deuteronomy also by John MacHale, later Archbishop of Tuam (1840). |

|

There is a version of the New Testament, published by Samuel Bagster and Sons, Dublin, 1858, translated by Riobeard O'Cathain of County Clair. Nothing else is known of this man. |

|

A Gaelic Gospel of Mark. Largely based on the Gospel of Mark in Ewen MacEachan's New Testament. The New Testament was produced in 1875 from a manuscript left by Father MacEachan. Archaic language has been replaced by modern words and idioms. |

|

The Manx Gaelic Scripture portions is found here. They include Esther, Jonah, Matthew, Luke, and John. Manx was spoken on the Isle of Man in Great Britain. Today, Manx has no native speakers. |

|

In 1946 and 1952 Cosslett Ó Cuinn, (a Protestant clergyman interested in Irish, especially the moribund dialects of today's Northern Ireland) translated the New Testament into more modern Irish. It is comparable is translation technique to the Revised Standard Version in English, and is more Ulster Irish than anything else. |

|

Another translation, called the Maynooth Bible (1981) was printed, but nothing is available yet on this translation. |

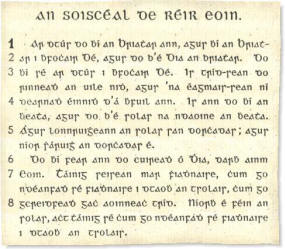

The Irish 'Joynt' version of the

New Testament. |

Some Scripture texts translated into modern Irish.